What is a Living Wage?

It should be earned in a standard work-week of no more than 48 hours, and must include enough to pay for food, water, housing, education, health care, transportation, clothing and some discretionary earnings, including savings for unexpected events.

Why the minimum wage is not enough.

Legal minimum wages in garment-producing countries all over the world fall short of a living wage, meaning garment workers are unable to provide the most basic needs for themselves and their families. The gap between the legal minimum wage and a living wage is ever growing. In many countries, the minimum wage falls far short of the living wage. In Asia, the minimum wage can range from 21% (Bangladesh) to about 46% (China) of a living wage (research 2019). In European production countries, we see sometimes even larger gaps, from 10% (Georgia) to 40% in Hungary.

There are a number of countries that have no legal minimum wage at all. Governments of producing countries have no incentive to raise minimum wages, fearing that higher minimum wages will lead to brands shifting their orders to countries where labour costs even less. This is the reality of the fashion industry, which means minimum wages are never raised to subsistence level (in line with rising costs for basic needs). In addition to that: workers are often not fairly or not represented at all in the minimum wage bargaining process. In most countries where garments make up a significant part of exports, minimum wages have risen only very incrementally to adjust partially for inflation. These rises often come too late and are negligible: in Bangladesh, for example, the lowest paid workers are still earning only half of what they demanded and needed since 2016.

Living Wage Benchmarks

Calculating a living wage is not easy, although certainly not impossible. Several scholars, unions and labour rights groups have developed credible benchmarks for one or multiple countries or regions. A robust living-wage benchmark must be:

- Transparent in method and conclusion

- Revised on a regular basis to ensure inflation and rising costs of basic goods are taken into account.

- Established in negotiation with national or regional unions as not to increase wage competition.

- Enough to cover the full basic needs of a family, as a baseline, and allow for savings. This includes single mothers or workers without partners who are supporting two elderly relatives on one wage.

- A living wage benchmark should put a floor not a ceiling on wages. It should facilitate improvement beyond securing a minimum income for all workers.

Asia Floor Wage Alliance, Global Living Wage Coalition and Wage Indicator Foundation benchmarks are examples of benchmarks that meet this criteria. Fair Wear Foundation’s Wage Ladders which compare several benchmarks with local statutory minimum wages are another useful tool.

Savings and Survival

On their current wages, garment workers often have to make hard decisions about their health care or their children’s education. It is common for workers to faint from lack of nutrition since they often do not earn enough to feed themselves and their families adequately. The added stress of juggling bills and loans and lack of sleep from inhumane working hours has long term health consequences for millions of workers. Most will have to make a choice between buying food and paying to see a doctor.

Life is full of the unexpected. Earning a wage should give you enough security to face it. The fact that most workers in the garment and sportswear industry do not earn enough to cover life’s basic necessities means they cannot survive hard times. Covid-19 has made this glaringly obvious.Brands canceled orders to preserve their own cash flow, leaving the factories in their supply chain with not only no means to cover worker’s wages, but also no means to cover all other production costs. Many factories have shut down, firing thousands of workers.

Not only have brands been refusing to pay for orders already in production, sometimes even already in stores, they have also been offering consumers sales and discounts, leaving those at the bottom of the supply chain with nothing. Most workers are on the streets protesting for the wages they are owed since March, or they are being forced to go back to work without proper safety measures. Since they have no money they have no choice. Informal workers have been even more effected. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that 1.6 billion workers in the informal economy face massive damage to their livelihood after their entire business was decimated by Covid-19 restrictions.

All actors in fashion now understand the urgency and importance of re-imagining the industry and it’s business model. We want living wages to be at the forefront of this conversation. It’s time to rebuild the garment and sportswear industries to ensure fair pay for labour and job security across the whole supply chain.

For more information on Covid-19 .

Brand responsibility

Brands put forward all kinds of excuses for not committing to a living wage: that it is the responsibility of suppliers or governments, that it is impossible to pay as it would price them out of the market, that consumers don’t want to pay more, that there is no consensus on how to calculate it, etc. But while production can be outsourced, the responsibility to respect human rights and pay a living wage remains with the brand.

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UN Guiding Principles), clearly states the role and responsibilities of businesses and states (Governments).

The UN Guiding Principles are based on three pillars:

- The state duty to protect human rights

- The corporate responsibility to respect human rights

- Access to remedy

This establishes a principle of shared responsibility between the state and business, meaning governments have an obligation to protect the human right to a living wage by setting the legal minimum wage on a subsistence level, and businesses have to respect the human right to earn living wages accordingly.

The framework also clearly states that the responsibility to respect human rights “exists independently of States’ abilities and/or willingness to fulfill their own human rights obligations, and does not diminish those obligations. And it exists over and above compliance with national laws and regulations protecting human rights.” In other words, in cases where governments fail to protect human rights – such as when the legal minimum wage fails to meet the minimum subsistence level (a living wage) – businesses still have an obligation to respect the human right to a living wage by remedying this state failure.

The UN Guiding Principles establish supply chain responsibility. Any production company is responsible for all human-rights impacts across its supply chain, independent of where the human rights abuse occurs (i.e. in their own facilities, with sub-contracted factories, or with homeworkers). So while production of garments is often outsourced, the responsibility remains with each corporation and cannot be delegated and outsourced down the supply chain.

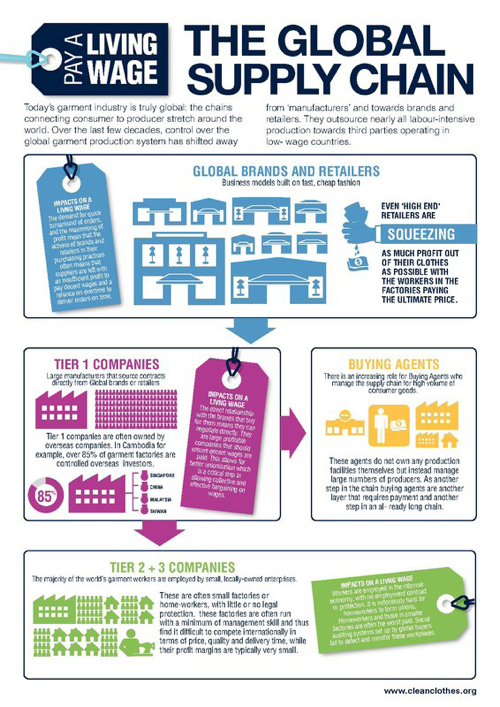

Why do we talk about paying factories not workers?

Brands do not pay workers directly. They pay their suppliers, who then pay garment workers. A supply chain is usually broken up into 3 tiers of supplier companies. Tier 1 supplier companies are usually commissioned directly by brands for production contracts. These tier 1 companies will subcontract work to other suppliers.

Suppliers are forced to estimate the lowest possible cost of production per item to bargain with brands for production contracts.This price is supposed to be enough for factory running costs, including rent, electricity, water and maintenance, material costs,shipping, a profit margin for the factory and cover all labour costs. To compete with the other tier 1 companies, suppliers project labour costs based upon minimum wages, rather than living wages; and ten-hour days, including two hours of overtime, rather than eight-hour working days.

Current purchasing practices reflect the rise of fast fashion. Where the norm was previously four style seasons per year, the brand Zara pioneered changing styles monthly. Most high-street brands now produce 52 ‘micro-seasons’ a year. Brands will also suddenly order twice as much of their popular items. This high turn over of product, coupled with uncertain order quantities has produced the current industry model. The uncertainty caused by buyer purchasing practices is then displaced upon workers through the use of flexible job contracts, unemployment during fluctuations in production, and downward pressure on wages.

Brands need to take responsibility to modify their purchasing practices to ensure their suppliers can pay their workers. We will continue to work with worker organisations and unions to ensure these changes are effective.

Unions and Worker committees

Workers have little to no power to fight for better wages. Freedom of Association (FOA) is under immense pressure and busting unions who are fighting for higher wages is anything but unusual in many garment producing countries. There has also been a remarkable increase in the number of worker committees established in the place of unions at factory level over the past couple of years. This creates the false impression that today’s workers are both organised and powerful. Brands often claim that worker committees and trade unions are essentially the same, which might only be true in a small percentage of cases.

Instead of promoting fair worker representation at factory level, it's often more appealing to brands, suppliers and local governments to support alternative structures that give workers significantly less power. Worker committees often involve factory management, which undermines garment workers' right to organise free of involvement by their government or employer. Additionally, in some countries, like in Bangladesh, worker committees are not allowed - by law - to bargain on wages, whereas trade unions are. Ultimately this means that the price brands pay for production is protected.

We want brands to do more to support the workers in their supply chain. Collecting data on unions and worker committees will give a clearer picture of the causes and consequences of human rights abuses in garment and sportswear production.

Read more about FOA.